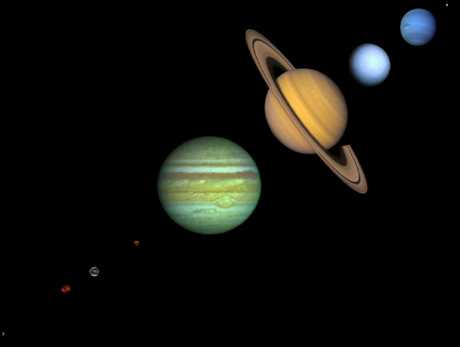

The Apparent Motions of Planets on the Celestial Sphere

The Apparent Motions of Planets on the Celestial Sphere

Two observations concerning the planets were very difficult to explain for

astronomers of the Middle Ages:

A major reason for the difficulty of explaining these features was the dominance of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BC) on medieval thought. Aristotle wrote on many things but was not really a scientist. He tried to combine observations with largely unfounded ideas that he believed were obvious and could be taken as first principles. He then tried to understand within this philosophical rather than scientific approach.

Aristotle's philosophy, building on Plato, held that the heavens were more perfect than the Earth, and that objects in the heavens were unchanging. As part of this philosophy, it was believed that the only motion permitted objects in the heavens was uniform circular motion (motion at constant angular speed on a circle), because such motion brought one back cyclically to the starting point and therefore was (in a sense) unchanging.

This philosophy had no problem with the direct motion of the planets, since that could be explained by uniform circular motion of the planets about the Earth (which, as any fool who looked at the sky could see, was clearly the center of the Universe =GEOCENTRICITY). However, neither the varying brightness of the planets, nor the occasional retrograde motion of the planets on the celestial sphere, were easily reconciled with this idea of unchanging objects executing uniform circular motion in the heavens.